If the Declaration of Independence is the first lesson in the Art of "Pencil Whippin," we missed it!

- Jul 10, 2021

- 8 min read

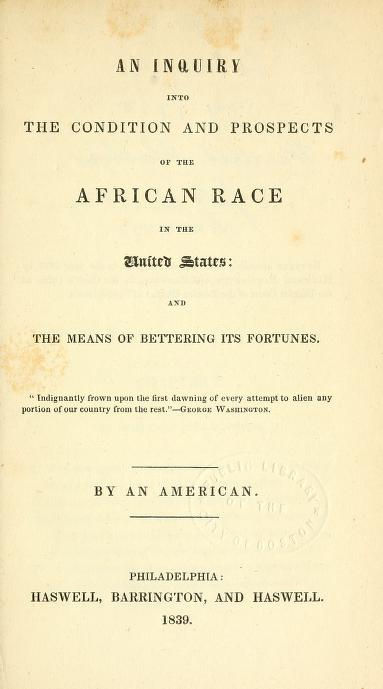

I'm on my "Why'd July!" , and even in the midst of the scared little guys that hide because they know they lied, and the story of Washington and the Declaration of Independence are the first lessons treasured up in the memory by American youth; and one of the first subjects on which the reasoning powers are exerted, is an attempt to reconcile slavery with the declaration that all men " are created free and equal," and "entitled to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. "The youth of ingenuous disposition, educated in the free states, in reflecting upon this subject, early obtains a deep impression of the fallibility and inconsistency of human character.

First, all men are free and equal; secondly, some of the men most distinguished in American history were slaveholders, that is, bought and sold their fellow-men like cattle; thirdly, among these distinguished men, some (as the author of the Declaration of Independence) condemned slavery in the strongest terms of language while they lived, and others, (as General Washington,) in their final acts, cancelled the obligation of the slave, and gave him freedom.

These reflections greatly puzzled the writer

The following pages in his boyhood, and induced a spirit of inquiry on the subject of American slavery, which has increased with maturer age. In common with the youth of the free states, he early imbibed a strong prejudice against slavery, as being incompatible with the freedom of our government: although this prejudice was subsequently somewhat softened, by reflecting, that some of the men whom Americans are taught from their childhood to venerate as great and good, were slaveholders; and also, by the consideration that the government, in all its acts and subordinate departments, has, (until very recently at least) recognised the lawfulness of slavery. There are multitudes, doubtless, at the North, who will at once comprehend the embarrassment of the writer at this period, by their own experience; fully convinced of the wrong of slavery as an abstract question, and yet notfeehng authorized to openly denounce it, under the circumstances in which it is tolerated in our country: and it was not until the writer had mingled with slavery, and observed its practical operation and bearing upon the community, with a circumspection prompted by the curiosity and unsatisfied inquiries of twenty years' residence in the free sates, that he was enabled to form an opinion of its merits, as it exists in the United States, and also to see the reason why great men had been engaged in it, and why the people of the South so tenaciously adhered to the practice. The result of these observations is given in the following pages; and the writer

Feels an anxious interest in the diffusion of information on this subject at this time, for two reasons:

1st. A crisis is approaching. Every man of common observation must be aware of the fact, that this subject, the moral and political influence of slavery, has been increasing in public interest for the last few years; and there are evidently causes at work, which will continue to increase this interest, until public opinion shall be centred upon it with a force, which can neither be evaded nor repulsed. The rancor of a most bitter political strife has for a time withdrawn public attention from it, but the elements are yet in a state of commotion, and only wait a favourable opportunity to burst forth and overspread the whole horizon. And no honest man can, in view of our national interests, wish the settlement of this great question delayed. If slavery is that grievous, heaven-daring oppression, which some of its opposers are clamorous in denouncing, it should be speedily abolished; if it can be shown that the practice is consistent with republicanism and Christianity, the slaveholder should be relieved of that load of obloquy which many now heap upon him, and be permitted to hold his possession in peace.

2nd. I call the attention of southern men to this point. Free discussion is the only method of eliciting light, and establishing correct principles in this land of liberty. We have here no absolute monarch to think, and speak, and act for the people "by the grace of God." Free discussion is not only the prerogative but the genius of our people. It is the great manufactory of pubic opinion, which is the supreme law of the land. Every question, whether of village or national notoriety, must be submitted to it, and decided by it. It is as impossible to prevent this as to stop water from running down a declivity; and the attempt to arrest the progress of discussion on this great subject, if persisted in, must lead to the most disastrous results. A practice that will not bear investigation is always liable to suspicion. If the South are determined to resist every attempt to discuss and investigate the merits of slavery, it will not only increase the prejudice of its opposers, but the consequence will be to produce rival orders of public opinion at the North and South, diametrically opposed to each other, and tending to cherish sectional and jarring interests.

Without a free interchange of sentiment, there cannot be such an enlightened understanding of the subject as will lead to a righteous decision by this people. Even now there are many anxious minds labouring under an impression that slave-holders are unwilling to bring the question of slavery to a free and full discussion of its merits; and this impression is strengthened by the acts of tlie national legislature. At both the sessions of the twenty-fifth Congress, the House of Representatives voted (after much animated and excited debate) to reject all petitions, and to allow no discussion on the subject of slavery. This act is to be regretted. Its policy is more than questionable: it is unwise. It is like checking a current in its natural channel: the accumulated waters may be arrested for a time, but when the barrier gives way, as it surely must, the torrent will sweep every thing in its course. The calm which seems to acquiesce in this act, is no evidence of its approval. The fires are becoming more intense in the pent up volcano. On a subject not involving the safety of the dearest interests of the community, a reflecting people will yield an unwilling assent to the decision of a large majority, and submit to the rejection of their petitions, constitutionally expressed and offered; until the manifest justice of their cause, and the exertions of its friends, have removed the opposition to their wishes. This mode of rejecting petitions is manifestly unjust, contrary to the spirit and letter of the constitution, and can only be defended on the ground that extreme exigences warrant the setting aside of established constitutional provisions. The slaveholder pleads that the reckless violence of the abolitionists has produced this result, and no doubt this is true; but whether the ultimate decision of the country will sustain the act, and thereby declare that the exigence required the sacrifice, time only can determine. It cannot be questioned that one effect of this act will be, a stronger conviction among the people of the North, that the South are inclined to shut up every avenue to the investigation of slavery. And the final consequences of such a conviction at the North, or such a determination at the South none can foresee, but all must dread.

The object of the writer is to diffuse information on the subject among the popular ranks of his countrymen.

Many books have been already written on both sides of the question; but they have generally been elaborate treatises: on one side condemning slavery on the abstract principles of moral right, or on the other defending the practice, from the usages of mankind in all agps; or by denying and controverting the opinions of their opponents. Such works are but little suited to the popular taste, and produce but little practical effect upon the body of society. The great mass of the people, the owners and cultivators of the soil, and the artizans men who acquire a proud independence by honest and persevering toil, who are seldom concerned in tumults or mobbish excesses, and to whom demagogues and enthusiasts generally preach in vain, a class of men to stand by the laws in the hour of peril, and which holds in check that spirit of insubordination, which seems eager to destroy, these are the men, who are to pronounce sentence upon this momentous subject; and the sentence they pronounce they will carry into execution. But they will not decide this question, however enthusiasm may invoke, or uncurbed passion may menace, until they have had opportunity to ascertain facts, to hear evidence, and weigh the subject in all its bearings. They constitute the supreme court of the country, from whose decision there is no appeal. These men have little knowledge of Latin, or the logic of the schools, and little time to study the elaborate productions of doctors of law or metaphysics. With them a well attested fact is of more value than a cart load of suppositions; and their assent is given to theory, when it is reduced to practice.

They require no other wisdom than that plain sense with which God has endowed them, and which their observation and industry keep in constant exercise and improvement to decide upon the most important subjects of national interest when fairly brought to their comprehension.

To this class of his fellow countrymen, both North and South, the writer addresses these pages, without reference to politics, party, sect, or section. They have an unspeakable interest in this question; for it needs not the spirit of prophecy to foretell, that unless it be amicably settled, a crisis is approaching, which will involve the whole country, and come home to every man's bosom, from Maine to the Sabine.

Already the agitation is begun, and a spirit is awakened which cannot be put to rest, till a final verdict is rendered by the people. Notwithstanding the magnitude of the subject, it is becoming one of absorbing interest, and every man in the nation must look it in the face.

To prepare the public to act understandingly, it is important that information should be diffused. Already, from ignorance of each other's circumstances, sectional animosity is gaining ground; and it will require all the wisdom which fallible men can gain from moral obligation and experience, to arrest the current of sectional prejudice, and decide the question in the spirit of equity, and with reference to the great interests at stake. That the great mass of the people are ignorant of each other's situation, and sectional and domestic customs, and therefore greatly liable to err in judging of them, the writer is abundantly satisfied from his own experience and views, before and after witnessing the operation of slavery. Should he be instrumental in directing this class of men to a sober and righteous decision on this momentous subject, his object will be attained. He has no selfish motives to favor. His own individual suggestions are alone responsible for this work. He has consulted no man, and but few books. He has no interests at stake, which will be involved by the decision of this question, any farther than as a single member of the community. The subject has been one of engrossing interest to him ever since he came to years of manhood, and he has watched the progress and development of public sentiment with great solicitude. His humble efforts are intended to direct it, in its inquiries, to a sober and thorough investigation; to a just, and, if possible, an amicable settlement of the momentous controversy.

This is my beginning of my Saturday solutions ,

assante,

Comments